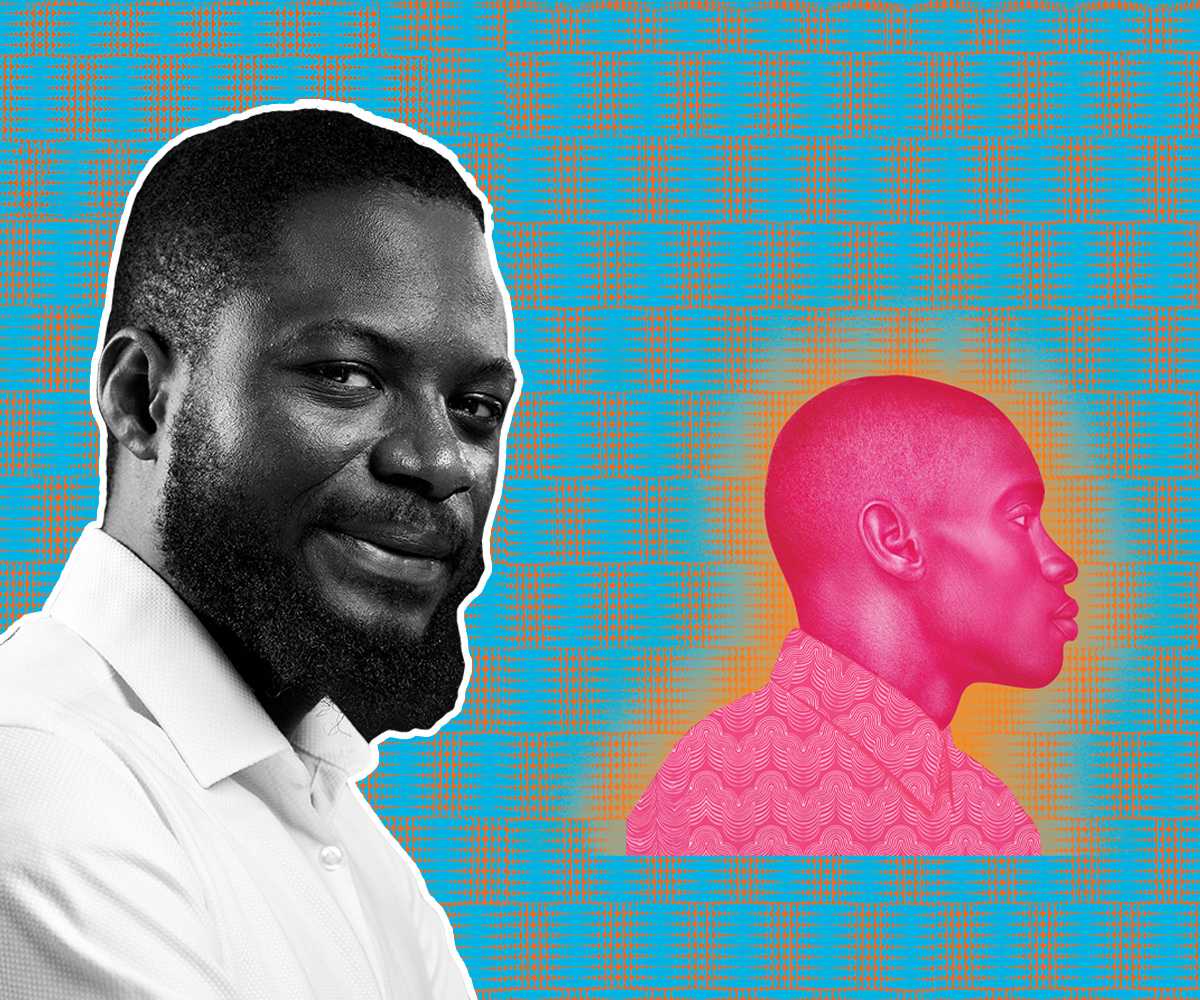

Director Ike Nnaebue / Photo credit: Jide Tom Akinleminu

Film

No U-Turn: Exploring The Tough Realities of African Migration

Director Ike Nnaebue / Photo credit: Jide Tom Akinleminu

No U-Turn captures the perilous journey thousands of Africans take every year to Europe and why they deem the risk worth it

By Takunda Chimutashu

October 2023

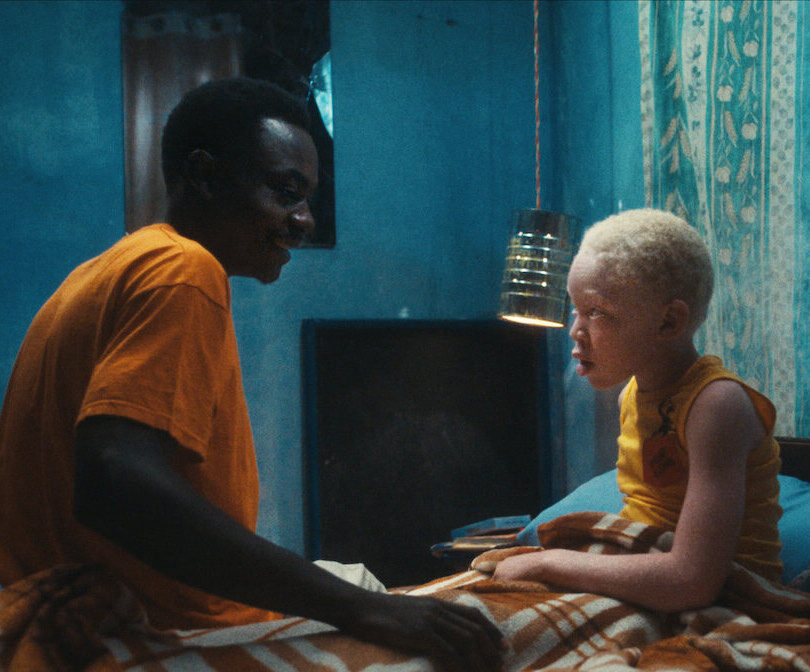

No U-Turn, released earlier this year, follows a poor 20-year-old, who attempts to illegally migrate to Europe by road to seek a better life. In the film, director Ike Nnaebue retraces his steps as a young illegal immigrant, “I had finished my apprenticeship, and I was stranded with no startup capital to start my business. I was frustrated and hopeless.” Nnaebue continues, “So, when I heard that it was possible to travel to Europe by road without a visa and with very little money, I thought that was exactly what I needed,” he added.

Originally hoping to make money and return to Nigeria, Nnaebue quickly discovered it wasn’t as easy as he was told.

“The desert is a deadly place, and crossing it is almost impossible without being kidnapped. People are being sold into slavery and forced to pay their own ransom. Then, when they eventually get through that and make it to North Africa, they are faced with a different kind of suffering as well. The Mediterranean Sea itself has become the biggest graveyard in the world,” he says.

Nevertheless, people continue to migrate to Europe for a better life. A report by UNICEF places the number of children who die at the Central Mediterranean Sea weekly at eleven, with an estimated 11,600 children having made the dangerous crossing so far in 2023.

Nnaebue’s experience, and that of many West African migrants trying to find safety and a better life in Europe through what is referred to as “the back door,” led the filmmaker to create No U-Turn. “The doc is me retracing the journey I took in my late teens, 27 years ago. It is an opportunity to go back and understand the decision I made. “I [always] wanted to go back [to Europe], and then I realized that 27 years later, people are still trying to go through that route despite the dangers.”

This journey itself led him to filmmaking. He describes how patient he had to be and how he waited for the right opportunity before starting this journey.

“I also wanted the European audience to understand that migrants are humans with valid dreams and aspirations, just like any other person in other parts of the world. If anybody has ever thought of moving from New York to New Jersey or Houston to Atlanta for a better life, it’s really no different between that and a migrant who thinks they would find better opportunities in Europe.”

There have been articles documenting what it means for Africans who migrate through the dangerous routes from Nigeria to Benin to Morocco, but with No U-Turn, we don’t only hear the stories from these people, but we see how their lives are impacted by their decision to migrate to Europe. For audiences, the journey is equally as emotional, leaving us with the memory of their faces and their stories every time a news outlet recounts a migration tragedy.

It’s a documentary filled with African voices, which Nnaebue says was the goal. “The film was part of a cohort called Generation Africa, founded by the amazing people at Steps, South Africa — a collective of African filmmakers who were encouraged to tell different stories around migration. The goal was to help African voices be heard worldwide instead of African stories being told by non-Africans,” he told STATEMENT. “Steps and Generation Africa helped with the entire fundraising process and were instrumental in the process of making this film.”

While Nnaebue agrees that many people who leave, do so seeking greener pastures, they also decide to leave in part because of the suffering back home. This understanding has led him to be part of a project called “Returning Migrants Reintegration Project,” to provide a safe space, support, and whatever they need when they come back to the continent. “That’s why many people would rather languish in the desert than come home because they don’t have anything to return to. So we want them to know they have a home to return to. We want to help them recalibrate their lives.”

The filmmaker has come a long way since his journey in 1998. He recognizes that he was fortunate enough to have not attempted it more than once. “I recently met somebody who said he would rather die on the road than go back home, and that’s sad. It paints a picture of what Africa has become over the years, where things are getting worse for a majority of the populace instead of things getting better, which is why we’re doing this work. We want everybody to care enough and bring their attention to it.”

No U-Turn had its festival run in 2022 and the first few months of 2023 at the New African Film Festival, the Human Rights Watch Film Festival, Berlin International Film Festival, where it won a special jury mention award, and FESPACO where it won the best film on ECOWAS Integration.