In recent years, African films have gained well deserved recognition at the most prestigious international film festivals. There was a time when festivals like Sundance, Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF), and Tribeca Film Festival predominantly showcased Western productions, but the tides have changed. These festivals are now embracing a rich tapestry of narratives and talents from the African continent, signifying a remarkable turning point in the world of cinema, as African filmmakers receive their long-overdue spotlight on the global stage.

At the heart of this burgeoning success is a new generation of African filmmakers who have unleashed their creativity, ingenuity, and cultural perspectives to captivate audiences worldwide. From Kenya to Nigeria, Ghana to South Africa, and beyond, these filmmakers have woven tales that are both unique and universally resonant. Their films celebrate diverse identities, explore poignant social issues, and offer glimpses into African traditions, all while challenging outdated stereotypes and tropes.

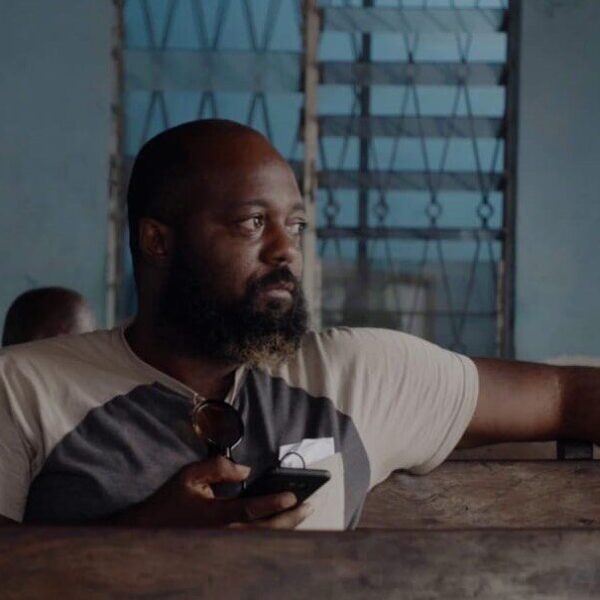

Sundance, once a haven for independent American cinema, has now become a melting pot of global talent with African films capturing the attention of audiences and industry professionals alike. This year, several African films received critical acclaim at the Utah-based festival including CJ Obasi’s Mami Wata and Sofia Alaoui’s Animalia, two films that won jury prizes at the festival.

African films are increasingly finding their place in this cinematic haven, capturing the attention of audiences and industry professionals alike. One such personal essay film, Milisuthando by South African director Milisuthando Bongela, left a profound impact at Sundance with its evocative storytelling of the apartheid regime in South Africa and negotiating the complex world against the backdrop of post-apartheid South Africa.

For Love Nafi, a DMV-based native, African entertainment as a whole, is getting its just recognition, although there are still some challenges.

“Similar to Africa’s takeover of music, African cinema has definitely permeated the global stage and I feel that there’s a budding amount of exceptional films gaining traction and being recognized at major film festivals,” Love Nafi said. “However, equity and representation within these mediums can sometimes still remain an issue. While African films are being included, all of our stories aren’t necessarily being amplified in comparison to our counterparts. As a whole, I think it’s important for Africa to continue to find ways to create its own stage.”

The Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF) has also embraced the richness of African cinema. In the festival’s Africa Hub, an exclusive platform dedicated to African films, vibrant voices from the continent resonate across the world, and festival goers this year will have the opportunity of seeing many of such films by talented African filmmakers, including I Do Not Come to You By Chance, executive produced by Nigerian veteran actress and producer, Genevive Nnaji.

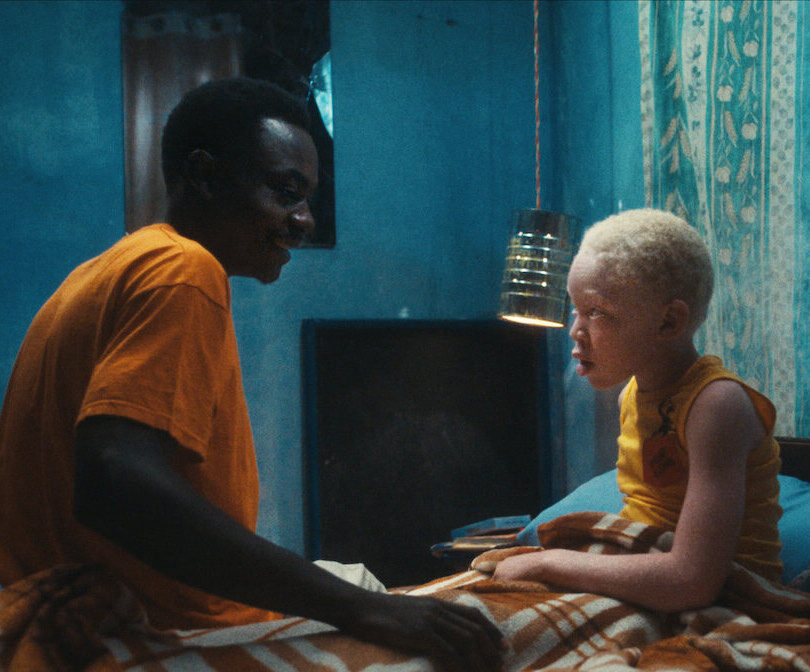

Tribeca, nestled in the vibrant heart of New York City, has also embraced the renaissance of African cinema. The festival has demonstrated its commitment to showcasing the diversity of African stories, be they tales of urban life, ancient folklore, or historical events. Nigerian Prince by Nigerian director Faraday Okoro stunned Tribeca audiences with its portrayal of a troubled American teenager Eze, who is sent away to his mother’s native Nigeria against his will, and gets entangled in a web of criminal activity. Okoro’s masterful direction, combined with a compelling screenplay, unraveled the temptations and showcased his grip on artistic direction.

The rise of African cinema has not occurred in isolation but as a result of concerted efforts from both filmmakers and festival organizers.

Uwe Boll, a German filmmaker, who has become renowned for his adaptations of video game franchises says that Africa is gaining a grip. “This year, at Cannes it was all about Africa, one of the most discussed and hyped continents. More than five films ran at the festival and in the market even more — which is fantastic,” he said.

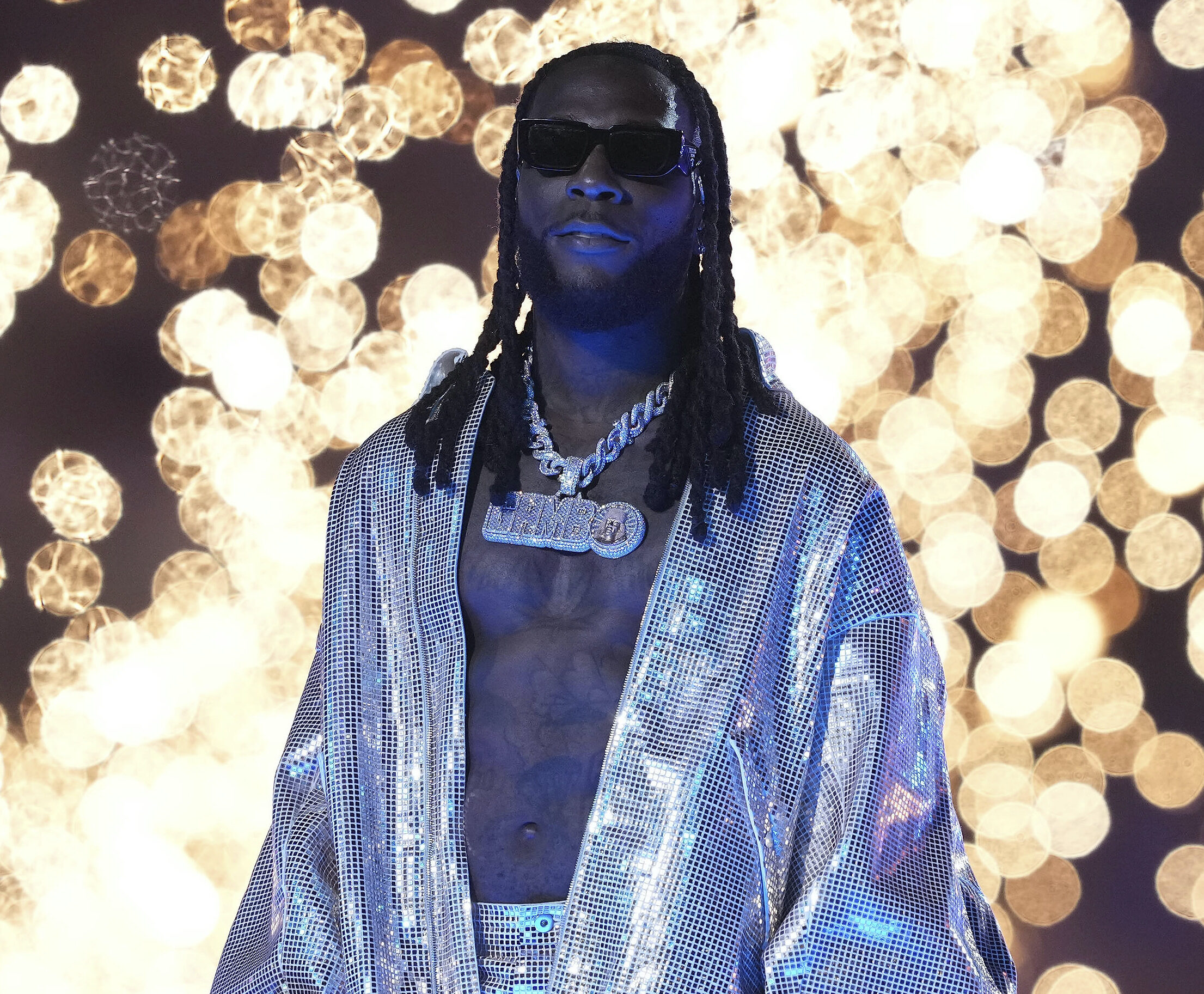

Four Daughters, crafted by the visionary Tunisian director Kaouther Ben Hania — renowned for The Man Who Sold His Skin, along with Banel & Adama, the remarkable inaugural work by Senegalese-French filmmaker Ramata-Toulaye Sy, formed an intriguing cinematic pair at the festival this year.

Boll also added that countries in the Middle East, such as Morocco and Tunisia, have been long-time active locations for various big Hollywood productions. “Movies like Mission Impossible or Gladiator have utilized several Middle Eastern locations to shoot, and recently, significant investment funds have been entering the scene, contributing millions of dollars to co-produce films.”

Another catalyst for the recognition of African films has been the growing demand for diverse narratives in the global film industry. Audiences hungry for fresh perspectives and untold stories have welcomed African films with open arms, eager to be transported to new worlds and immersed in rich cultural experiences. This demand has prompted film distributors and streaming platforms to acquire more African films, extending their reach to viewers across the globe. In 2022, Netflix and UNESCO collaborated on an African Folktales competition, which was a chance of a lifetime for rising Sub-Saharan African filmmakers and storytellers to breathe new life into ancient tales, flaunting their brilliance to the world in their very own languages by seizing the moment, rewriting the narrative, and embracing the global stage.

There’s also the co-productions between African filmmakers and global partners helping to bridge the gap and unravel African cinema to wider audiences. Elesin Oba, The King’s Horseman, a historical drama was co-produced by Ebonylife Films and Netflix. In 2022, it was selected for screening at TIFF and now streams globally on Netflix.

In spite of the resurgence of African films and the support African governments and institutions provide to local film industries — a UNESCO study shows that merely 19 out of 54 African countries provide financial support to filmmakers — there is still a long way to go in terms of funding and support, especially when many filmmakers across the continent encounter obstacles such as restrictions while filming.

Chrissy Collins, the Chief Communication Officer for Pan African Chamber of Commerce also agrees that there is still a long way to go.

“It’s a powerful step towards breaking stereotypes and fostering a deeper understanding of African cultures. However, we still have a long way to go and we must continue to support and uplift African filmmakers to ensure this progress is sustained and amplified,” Collins said. “This way, we can break the stero-typical films that Hollywood creates based on an americanized view of Africa.”

Beyond the immediate success at international festivals, the rise of African cinema has ignited a collective sense of pride and hope within the African film community. As a result of this newfound recognition, a new generation of filmmakers have been empowered to tell their stories. This cultural renaissance has sparked a virtuous cycle, nurturing a vibrant ecosystem that fosters creativity, innovation, and artistic expression across the continent.

According to Nataleah Hunter-Young, an International Programmer at the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF), African cinema has long been celebrated under the franchise.

“TIFF has had a long and unique history of spotlighting African cinema, so for us, the African presence isn’t new. We celebrated 25 years of that presence in 2020 with ‘Planet Africa 25’ screenings, panels and parties, much of which is documented online, but as the African industries on the continent grow, so too does their presence at the Festival, and that growth is reflected in the strength and creative breadth of the productions in each year’s Official Selection,” she said.

The entertainment landscape is evolving, and with that comes the increased demand for African stories. “What has changed, from a global perspective, might be the audience demand for African content and as a result, African creators are receiving more and more attention from European and North American industry stakeholders, particularly from streamers which is still the easiest way for North American audiences to watch African productions,” Hunter-Young added.

In spite of the expansion of the streaming era, Hunter-Young believes that streamers alone can’t dictate industry growth, so festivals will continue to play a major role in audience development and in pushing industry expectations.

The recognition of African films at these international festivals is not merely a matter of tokenism; it reflects a growing awareness of the exceptional talent emanating from the continent. Gone are the days when African cinema was limited to niche audiences or considered exotic novelties. Today, these films transcend cultural boundaries, resonating with viewers from all walks of life, igniting empathy, and fostering cross-cultural curiosity.