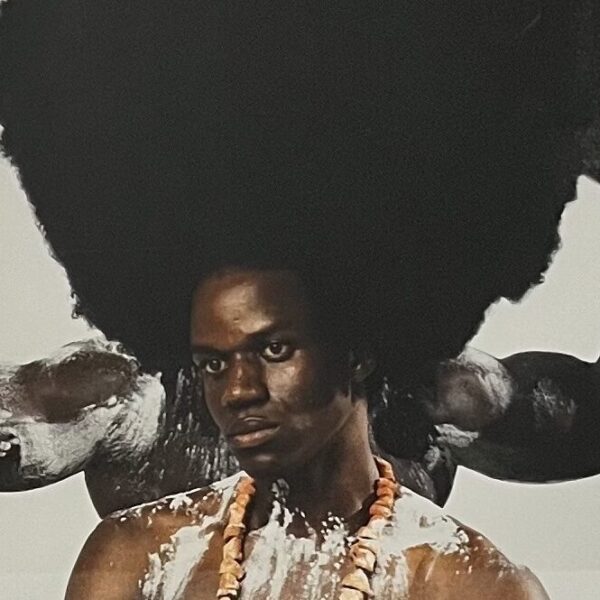

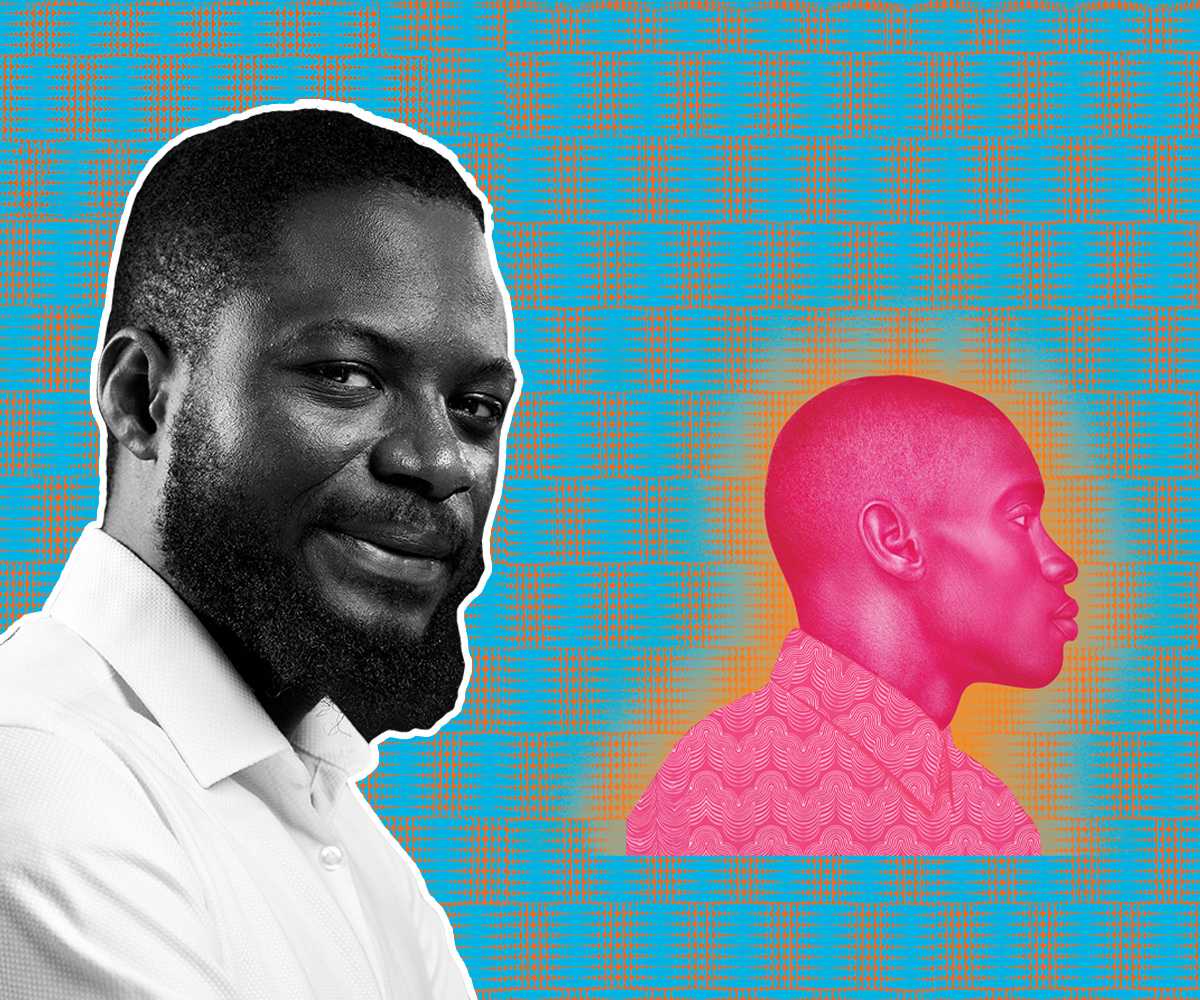

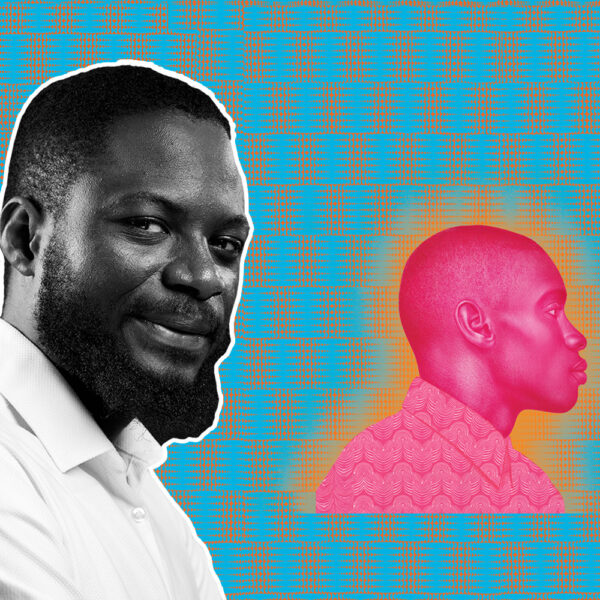

What is it like to live in the mind of a 15-year-old whose life has been formed by the intersection of Western pop culture and a Nigerian upbringing? Stephen Buoro’s novel, The Five Sorrowful Mysteries of Andy Africa, tells the engaging story in his acclaimed first novel. A recipient of the Booker Prize Foundation Scholarship, Buoro has a degree in Mathematics and an MA in Creative Writing from the University of East Anglia.

STATEMENT spoke to Buoro about his writing process (part of the novel was written on his Blackberry!), the novel’s themes of religion and Western pop culture, his favorite time to write, and more.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

STATEMENT: The Five Sorrowful Mysteries of Andy Africa is an interesting name for a novel. Can you tell us how you conceptualized the title and a little bit about the novel?

Buoro: The novel is a coming-of-age story set in present-day Nigeria. So it’s about Andrew Aziza, a smart, funny fifteen-year-old boy obsessed with blondes, whiteness, the west, and knowing who his true father is. He is ashamed of his mother, a photographer, who is poor and uneducated. In essence, the novel is about Andy’s feelings of shame and obsession intensifying when his life is suddenly destabilized by colonial violence.

Regarding the title, The Five Sorrowful Mysteries is a prayer of the rosary in the Catholic Church. I come from a Catholic background, so it’s a prayer I said a lot growing up in Nigeria. This prayer reflects on the final moments of Jesus’ life during his time on earth — carrying of the cross, crucifixion, and death. While writing this novel, I realized especially in the first draft, how the life of Andy and also many Nigerians I knew, strongly mirrored this prayer. The prayer seems to reflect the turbulence and suffering of the post colonial experience in a country like Nigeria trying to find stability. I’m very interested in intertextuality, and the prayer is very intertextual. I hope readers get to see the novel as a literary prayer.

A significant theme in the novel is the influence of the West on Andy’s taste in media — films like Star Wars, Dune — and literature and how his interests alienate him from his peers. Where did the idea for Andy’s alienation come from and does it mirror your own experiences growing up in any way?

Of course. I was born in 1993 in Nigeria, so I was a teenager in the 2000s, a period saturated with Western culture. Western culture became much more ubiquitous in the mid to late 2000s in the country due to the internet, and for a Nigerian kid like Andy, that brings a sense of being present on the global stage. I felt that way as a teenager too because my friends, classmates, and I would spend a good chunk of our time talking about cultural phenomenons like WWE, the Premier League, the new Will Smith and Angelina Jolie films, all that kind of stuff, so it mirrored my experience too.

Growing up, there was this huge presence of the legacy of colonialism; For example, we had to go to church and be religious, and we were told that this Western God and system of being are the right and only ways of doing things. And in school, I received similar messages because some of my schoolmates and I were flogged for speaking our local languages. So gradually, as a teenager, I began to absorb all these elements of the West such that my mates and I would mock other schoolmates who mispronounced English or French words. Partaking in Western culture was a way for me to belong because I didn’t want to be alienated from my peer group. All of that has huge imprints on young people and affected me when I was young as well. These huge imprints affect the way we conceptualize the world, our sense of self, and the way we see things in general and I wanted to explore all that through the character of Andy, his friends, and their interests in pop culture.

It can be argued that this novel doesn’t cater to Western audiences or coddle readers who may not understand its idiosyncrasies. For example, the untranslated Hausa used in the novel. Was this an intentional choice?

Definitely. I’ve always seen it as tautology or unwarranted repetitions when novels try to interpret certain expressions. I understand why many African writers have to do that and you will find a few points where I tried to translate some terminologies in the book too.

I think people will actually google stuff they care about when they’re reading, as many have access to Google translate and the internet. My intention for this novel was to try and use all the stylistic devices at my disposal to convey the experience of being a Nigerian boy growing up in the North, what he sees, hears, and the feel of the place.

Andy suffers a dreadful fate at the end of the novel and it almost feels deserved. Was it always inevitable?

In a way, yes because coming from the point of the view of the plot and his character, there just seemed to be this direction. From the very first sentence he declares his love for blondes and that already projects the narrative towards that end when he attempts to leave the country. On the other hand, I have this schema, the five sorrowful mysteries which is the prayer I’m working with, that directs me towards that end. These two narrative frameworks all coincide towards Andy’s attempt to leave and his failure at leaving. Sometimes the easiest solution is usually the best in terms of the plot development.

I found out from a previous interview that you were a mathematics teacher while you were in Nigeria. How did you balance the demands of that job with the task of honing your skills as a writer?

I taught for about seven months which is still a considerable amount of time. Luckily for me I was working part-time at the school so I only went in when I had classes to teach. I was also working as a research assistant for one of my lecturers at the university so that was helpful. I would teach during the day and write during the evenings which was great because that was my favorite time to write.

Mathematics plays a significant role in how Andy processes the hardship of living in Africa. What inspired your decision to incorporate mathematics into the storytelling?

When I was writing this novel, I realized how my interests in mathematics, pop culture, and religion would help and arm Andy with amazing tools for unraveling himself for the reader and contemplating the post-colonial world he finds himself in. When I was Andy’s age, I found mathematics and poetry therapeutic in many ways because they helped me negotiate my angst and rage as a teenager. So that gave me a method of attempting to understand things.

Do you have a routine for writing and what was your process for writing this book?

Hopefully, I will have a definite routine in the next ten years as this is my first novel, but I didn’t have one for writing this book. Everything has just been some form of experimentation and discovery for me. For example, part of this novel was written on a Blackberry Curve 2, pencil and paper, and then on a computer. I love writing in the evening– I don’t know, maybe it’s the time of day when my brain is much more relaxed or less critical of itself, so I drafted the novel mostly in the evenings but my process changed when I was revising. When I have deadlines I just have to make it work.

Do you often know the ending of a story when you start it?

The ending was mostly clear to me when I was about a quarter into the novel, and that greatly helped me. I like the sense that I know where a story is going, and it gave me confidence during the writing process

Do you have any advice for African writers currently working to be better storytellers?

This might sound [like a cliche], but in my experience, just keep writing, dreaming, reading, and thinking. Also I remember reading this wonderful advice by, I think, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, about how Nigerian writers should just write their own stories and not copy John Grisham or other Western writers. That’s also wonderful advice!

Are you optimistic about the future of Nigerian literature?

That’s the only thing in Nigeria I’m incredibly optimistic about. Nigeria is going through so much turbulence and, for a writer, it’s a wonderful time to be alive and to write. I recently read Tola Rotimi Abraham’s Black Sunday, a very wonderful book. In the past we only had Chimamanda Adichie and a few others but so many emerging writers are coming through and that’s really great.

What books would you consider your favorites?

The Brothers Karamazov by Fyodor Dostoevsky. On my shelf, I currently have Don Quixote by Miguel de Cervantes and The Unbearable Lightness of Being. Also 100 Years of Solitude, James Joyce’s Ulysses, and my favorite Adichie novel, Purple Hibiscus.

What authors have influenced you as a writer?

In terms of who influenced this novel, I have to mention Chinua Achebe. Reading him when I was a teenager was very important in my development. Also, A Clockwork Orange by Anthony Burgess. In terms of the tone and voice in my novel, this book was very influential.

Do you tend to read at all while working on a book or do you cut off any possible inspirational supply?

When I was writing this novel, I had a lot of free time to read books and some of them gave me crumbs that stimulated my mind. I had been writing the novel for about five years and it would’ve been absurd not to read any other book for that amount of time. I also watched TV dramas like The Wire, Lost– the wide span of characters, the sense of time etc. It’s amazing!

Do you have any favorite films?

I love the musical film, Chicago. The writing and humor is on point. I love Jazz so I loved the music as well. Also, 2001: A Space Odyssey and Blue is the Warmest Color.

What is your ideal reading experience?

I’m very open to reading anything. For me, the only test a book should pass is for it to engage me on an emotional, intellectual, and even aesthetic level. I want to be able to forget about my mundane life and be immersed in whatever world it is.

The Five Sorrowful Mysteries of Andy Africa is currently in stores.