Photo credit: AP

Music

Inside The Rise of African Culture

Photo credit: AP

New technology spurs cultural appreciation, helping Africa to foster a complex, honest global identity

By Wale Oloworekende

October 2023

When Canadian pop giant, Drake, hopped on the remix of Wizkid’s balmy 2014 hit, “Ojuelegba” in 2015 — he ignited a global interest in the burgeoning Afrobeats scene. The musical union was brokered by British-Nigerian rapper and entrepreneur, Skepta, and in the eight years since, Afrobeats—and African culture by extension—has taken off, setting the stage for the continent’s recognition as a rising power in music, fashion, art, and film.

African culture’s rise to global prominence has, undoubtedly, been powered by its ingenious acts that combine their homegrown identity with global ambition. But it’s the contributions of key players like Skepta and members of the African diaspora scattered across the world who serve as unofficial ambassadors that have enabled this international awakening.

“The African diaspora is the bridge between what’s happening internationally and on the ground in the continent,” Ronx Bamisedun, the VP of international Strategy and Artist Development at Love Renaissance, tells STATEMENT. “They’re well-traveled and are always on the move between where they live and their homeland, so they’re the ones showing their colleagues at work what’s happening or what talent to look out for.”

The African diaspora is largely responsible for the rise of Afrobeats as popular acts like Wizkid, Davido, and Burna Boy have steadily progressed from playing theater dates to selling out stadiums across Europe and North America. According to Bamisedun, the close involvement of the African diaspora with these acts comes from a place of pride in the culture. “10 years ago, it wasn’t cool to be African in America or the UK,” she explains. “In the past, you’d ask people where they were from, and they’d lie and say they were Jamaican when they were probably from Lagos because it wasn’t cool. Now because our creative currency is so strong, our music, food, and culture are traveling.”

While popular music from Africa has undoubtedly been a success, other art forms are gaining similar prominence. Visual artists with African origins like Victor Ehikhamenor, Amoako Boafo, Ayanfe Olarinde, and Kwesi Botchway, have received critical praise globally for their work across painting, sculpting, and design. Ghanaian culture reporter, Gameli Hamelo, says that the rise in popularity of work by these artists is linked to a desire to change the narrative about Africa. “It got to the stage where the diaspora got tired of the negative imagery that is typically associated with the continent,” he says. “They have the power and accessibility of the internet now and want to use it to tell the world more robust stories about the continent. Supporting the art and artists from Africa is one of the ways to do that and it helps to project a different image of the continent.”

Outsider financial support has historically meant that African artists have less control over their output and the frequent elevation of works that propagate colonial biases, but the diaspora’s renewed investment into the continent has enabled a new level of freedom. “The African diaspora is in a space where they have the power to control the narrative,” Hamelo adds. “In the past, that wasn’t the case because western institutions like the BBC and CNN were often the sole source of information about culture. Now it’s very different; you have people on YouTube, podcasts, X, and many social media platforms being the primary source of information for a new generation and it’s being used in the right way.”

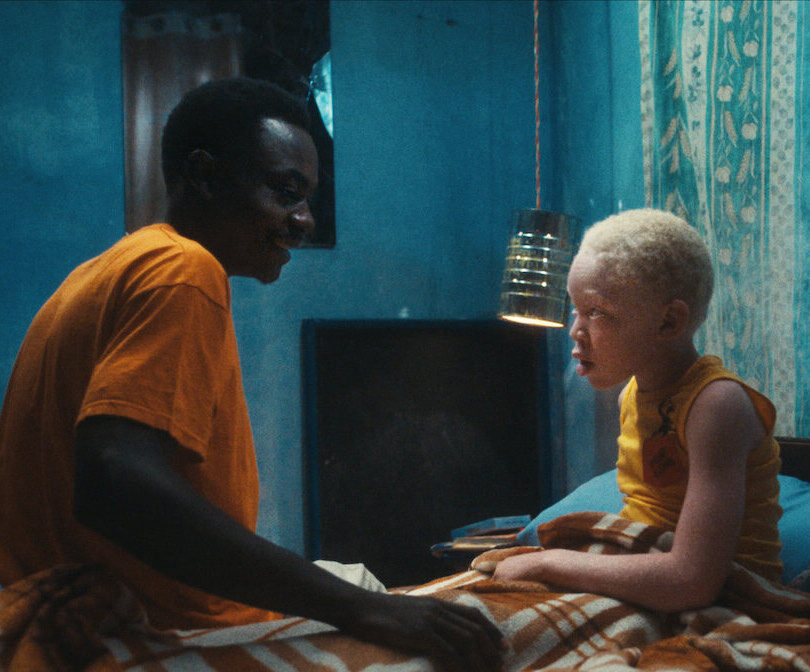

Technology continues to play a critical role in allowing African creatives to share their work with a global audience, find diasporan audiences who get behind this work, and ensure that it’s not lost to time. The arrival of streaming platforms, in film and music, has played a key role in helping to shape fuller and more contextual narratives around the African experience. “I think streaming is a powerful tool,” Nigerian-American filmmaker, Amarachi Nwosu, tells STATEMENT. “I think it’s amazing to have these different conglomerates invest in Africa.”

The investment made by Amazon Prime, Netflix, and Showmax allows African filmmakers to curate empathetic and multi-layered stories about the continent. “Even if you are in Japan and your friend doesn’t know anything about African filmmaking, you can go and show them films,” Nwosu says. “You can show them The Black Book and be like, ‘Hey. This is a really interesting film that tackles so many different narratives coming out of Nigeria. This is a story you should watch,’ and they can learn something from that experience.”

Ultimately, Nwosu believes that collaboration between the African diaspora and the continent is key to maintaining momentum going forward. “I think the African diaspora plays a role in just making sure that there’s an opportunity for the people that are the future storytellers,” she points out. “I think, on both sides, that I want to see an African diaspora that directly invests in the stories that we want to see come out of the continent, but I also want to see a continent that is equally engaged in stories from the African diaspora, especially these experiences of people who are navigating new terrains.”