Film & TV

How to Apply for African Development Funding for your Film or TV Project

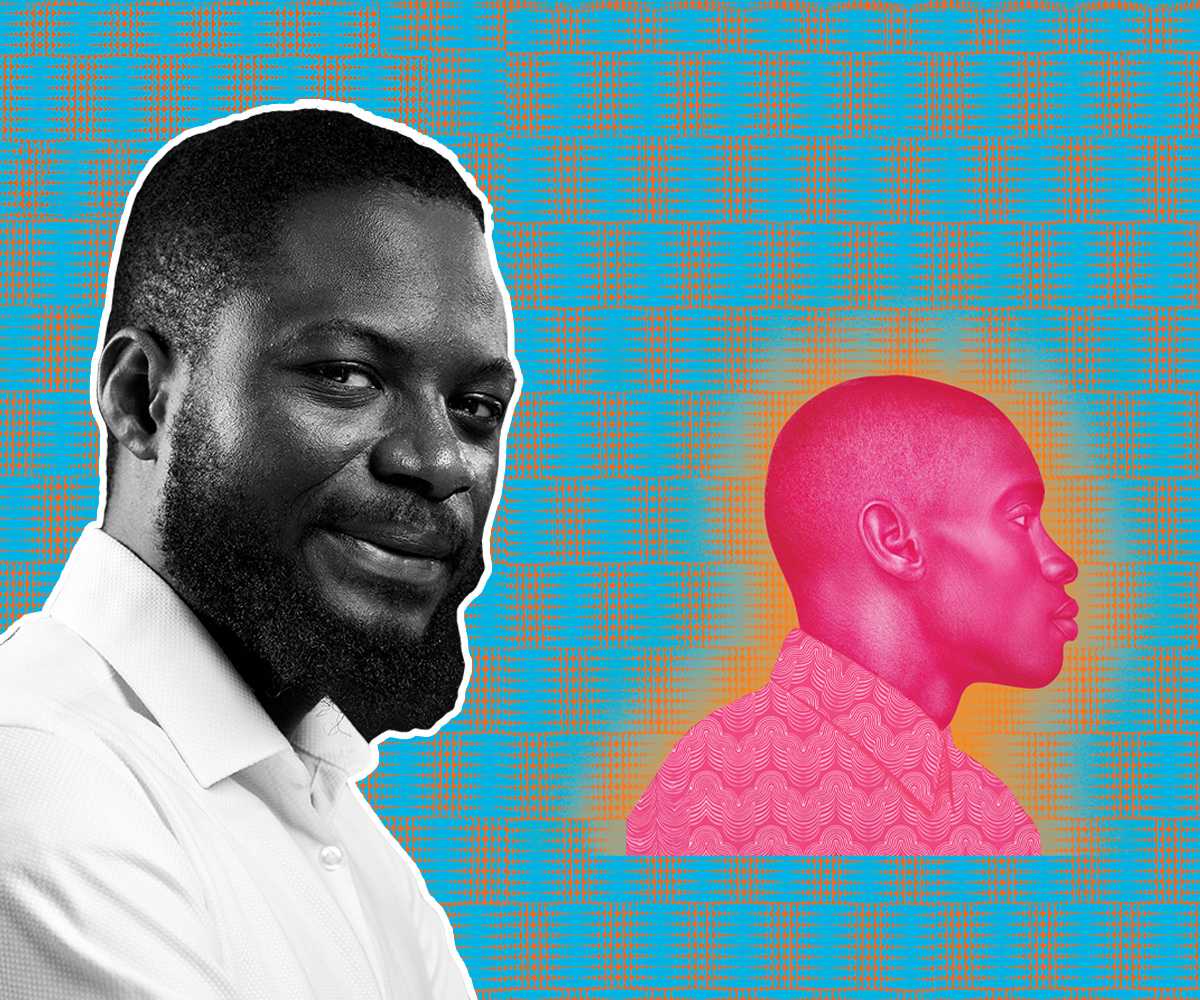

By Sughnen Yongo

July 2023

As an African filmmaker, applying for funding for your project can be daunting and downright intimidating. While it may seem as though the African filmmaking landscape is the best that it has ever been in recent years, with African films leaving their mark on the global landscape and more filmmakers gaining access to capital, obtaining the resources needed to fuel your dream may still seem far-fetched.

The film and television industry in Africa may be growing rapidly, but with that comes the need for additional funding to help projects move forward, and challenges still remain. According to UNESCO, across Africa, the leading challenge that exists for creators include weak or non-existent governmental incentives encouraging African creators to pursue their stories.

With the right funding, projects can further push the envelope and open more doors for the future. Fortunately, numerous African development funding sources are available for filmmakers and TV producers. To help filmmakers on the continent, STATEMENT has compiled a list below on how to apply for African development funding, some of the places to find them, and ways to go about it.

1. Understand African Development Funding

African development funding is a niche sector that hinges on regional organizations and philanthropic institutions to support creators in the arts and entertainment industry. These funds are frequently earmarked to support projects that advance cultural preservation, economic growth, job creation, and social impact. The Alter-Ciné Foundation offers several yearly grants to young filmmakers in Africa, Asia and Latin America to direct documentary films that tell important stories. The African Development Bank has also been on this wave for years. In 2023, the organization unveiled the iDICE program—an ambitious endeavor aimed at fostering the growth of digital and creative enterprises. With a staggering $618 million in investments, this initiative is one of the bank’s attempts to invest in African-powered creativity.

2. Find the Right Fit

An important step to take while applying for funding is to identify the right fit. A practical way to achieve this is to create a spreadsheet of every organization that offers funding, detailing the deadlines and the exact type of projects they’re looking for. This way, you can streamline your hunt and be more intentional about the process.

There are numerous organizations and charities that provide grants or other forms of financial assistance to African film and television projects, but the right fit is imperative. It’s important to do some digging to find the opportunity that aligns the most with your project. This way, there is a higher chance that you will get an approval. The IDFA Bertha Fund, for example, supports independent, critical, and artistic voices from Africa, Asia, Eastern Europe, Latin America and the Caribbean, and Oceania regions.

To secure a grant from an organization like this, you will need to ensure that your objectives are aligned by honing in on the organization’s mission and goal. This will provide valuable insight into their preferences and priorities, and the mission they are aiming to fulfill. In your application, it will also be important to highlight the potential impact your film can have on the organization’s target audience, and how it aligns with their goals. Highlight any research or data that supports the positive outcomes your film can achieve.

Showcasing opportunities for collaboration and partnerships with the organization by highlighting how your project can provide mutual benefits by involving the organization in various stages of the filmmaking process. This could include involving their members or beneficiaries as actors, consultants, or advisors, or providing opportunities for promotion or outreach through joint initiatives.

3. Know the Ropes

To navigate the world of African development funding effectively, it’s important to become a savvy investigator. Eligibility criteria differ for each competition or grant opportunity, so make sure you read each application thoroughly, so that you can share your work with investors in the most concise, yet effective way. Organizations like the African Development Bank (AfDB) are pouring into grants that foster creativity and freedom of cultural expression in budding filmmakers. On an international scale, the prestigious Sundance Institute offers several resources to creators including a grant that prioritizes films led by artists from Africa, China, India, Latin America, and the Middle East, according to its website. Creators living in the diaspora can also apply to this fee-free opportunity. By staying on the pulse of current funding programs, eligibility criteria, and application deadlines, you can increase your chances of securing financial support.

4. Build Relationships

In an industry built on collaboration and storytelling, investing time and effort into building relationships is not just important — it’s essential. Good old-fashioned relationship-building can help to foster trust, inspire creativity, and open doors to new opportunities. Strong relationships enable filmmakers to assemble talented teams, secure funding, access resources, and navigate the intricate web of the industry. A great way to navigate this is to keep your ear to the ground. Industry events like Sundance’s Collab online events that draw in creators globally to learn from, and engage with industry experts, network and get your name and brand out in the open. Another major event is the prestigious African Film Festival. It can get really expensive to attend these events, so it is a great idea to offer to volunteer at these events. Volunteering creates a win-win situation, because it gives you first-hand access to many film power players and other rising creators who are looking to get their name out.

5. Know Before You Go

Before crafting a proposal, it is imperative to know the pulse of your work. What do you stand for? What is the crux of the film or TV project? You need to also have a concise explanation for your work- an elevator pitch, if you will -that is compelling enough to draw attention. In crafting your pitch, be prepared to highlight an in-depth overview of the project, its goals, and its potential impact. Know the answers to questions about the project’s budget, timeline, and creative vision, because this will keep you ahead of the curve. Additionally, it is important to treat your project as a full – fledged business, and that means knowing, and highlighting any potential risks or challenges that may arise during the development and production of the project.